It’s a very recent habit when reading a book that I own – to mark the lines that mean something to me. Maybe if I ever lend the book to someone, they would know if we liked the same lines. Maybe if I read the book again when I’m older, it’ll be nice to compare notes with my younger self. Maybe I’ll never touch or open the book again and all I’m trying to do is leave as much of me as I can with book, as it will leave much of itself with me.

I finished reading Catch 22 twenty-four hours ago. I didn’t always have a highlighter pen with me, but the times I did, I sat and coloured the lines that moved me the most.

Twenty-four hours hence, I want to shout those lines out to the world.

- He was working hard at increasing his life span. He did it by cultivating boredom.

- Men went mad and were rewarded with medals.

- There were many principles in which Clevinger believed passionately. He was crazy.

- ‘Maybe a long life does have to be filled with many unpleasant conditions if it’s to seem long. But in that event, who wants one?’ ‘I do,’ Dunbar told him. ‘Why?’ Clevinger asked. ‘What else is there?‘

- Fortunately, just when things were blackest, the war broke out.

- ‘..I don’t think I’ll ever stop loving that girl. She was built like a dream..’

- Doc Daneeka rose without a word and moved his chair outside the tent, his back bowed by the compact kit of injustices that was his perpetual burden.

- Chief White Halfoat demanded with simulated belligerence..

- ..and the piercing obscenities they flung into the air every night from their separate places in the squadron rang against each other in the darkness romantically like mating calls of songbirds with dirty minds.

- ‘If you’re going to be shot, whose side do you expect me to be on?’

- ‘What could you do?’ Major Major asked himself again. What could you do with a man who looked you squarely in the eye and said he would rather die than be killed in combat, a man who was at least as mature and intelligent as you were and who you had to pretend was not? What could you say to him?

- ‘But suppose everybody on our side felt that way.’ ‘Then I’d certainly be a damned fool to feel any other way. Wouldn’t I?’

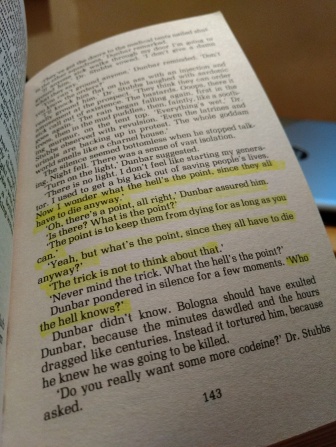

- ‘..I used to get a big kick out of saving people’s lives. Now I wonder what the hell’s the point, since they all have to die anyway.’ ‘Oh, there’s a point, all right,’ Dunbar assured him.’ ‘Is there? What is the point?’ ‘The point is to keep them from dying for as long as you can.’ ‘Yeah, but what’s the point, since they all have to die anyway?’ ‘The trick is not to think about that.’ ‘Never mind the trick. What the hell’s the point?’ Dunbar pondered in silence for a few moments. ‘Who the hell knows?’

- She was not interested in money or cameras. She was interested in fornication.

- There were strands of enlisted men molded in a curve around the three officers, as inflexible as lumps of wood, and four idle gravediggers in streaked fatigues lounging indifferently on spades near the shocking, incongruous heap of loose copper-red earth.

- Yossarian thought he knew why Nately’s whore held him responsible for Nately’s death and wanted to kill him. Why the hell shouldn’t she? It was a man’s world, and she and everyone younger had every right to blame him and everyone older for every unnatural tragedy that befell them; just as she, even in her grief, was to blame for every man-made misery that landed on her kid sister and on all other children behind her. Someone had to do something sometime. Every victim was a culprit, every culprit a victim, and somebody had to stand up sometime to try to break the lousy chain of inherited habit that was imperiling them all. In parts of Africa little boys were still stolen away by adult slave traders and sold for money to men who disemboweled them and ate them. Yossarian marveled that children could suffer such barbaric sacrifice without evincing the slightest hint of fear or pain. He took it for granted that they did submit so stoically. If not, he reasoned, the custom would certainly have died, for no craving for wealth or immortality could be so great, he felt, as to subsist on the sorrow of children.

-

The night was raw. A boy in a thin shirt and thin tattered trousers walked out of the darkness on bare feet. The boy had black hair and needed a haircut and shoes and socks. His sickly face was pale and sad. His feet made grisly, soft, sucking sounds in the rain puddles on the wet pavement as he passed, and Yossarian was moved by such intense pity for his poverty that he wanted to smash his pale, sad, sickly face with his fist and knock him out of existence because he brought to mind all the pale, sad, sickly children in Italy that same night who needed haircuts and needed shoes and socks. He made Yossarian think of cripples and of cold and hungry men and women, and of all the dumb, passive, devout mothers with catatonic eyes nursing infants outdoors that same night with chilled animal udders bared insensibly to that same raw rain. Cows. Almost on cue, a nursing mother padded past holding an infant in black rags, and Yossarian wanted to smash her too, because she reminded him of the barefoot boy in the thin shirt and thin, tattered trousers and of all the shivering, stupefying misery in a world that never yet had provided enough heat and food and justice for all but an ingenious and unscrupulous handful. What a lousy earth! He wondered how many people were destitute that same night even in his own prosperous country, how many homes were shanties, how many husbands were drunk and wives socked, and how many children were bullied, abused or abandoned. How many families hungered for food they could not afford to buy? How many hearts were broken? How many suicides would take place that same night, how many people would go insane? How many cockroaches and landlords would triumph? How many winners were losers, successes failures, rich men poor men? How many wise guys were stupid? How many happy endings were unhappy endings? How many honest men were liars, brave men cowards, loyal men traitors, how many sainted men were corrupt, how many people in positions of trust had sold their souls to blackguards for petty cash, how many had never had souls? How many straight-and-narrow paths were crooked paths? How many best families were worst families and how many good people were bad people? When you added them all up and then subtracted, you might be left with only the children, and perhaps with Albert Einstein and an old violinist or sculptor somewhere.

I can’t remember the last time that I both loved and hated a book so much, in equal measure, at the same time. Joseph Heller sure knew his way around the human mind as he did around words. Fin!